In every room of my* cafe is an artwork by the same artist. Three luscious, dreamy pieces that look like family photos. They are warm, calm scenes of memories locked in time. One is a rug, stuck on the wall. One is a painting on wood. One is embroidery. All three feature the artist’s grandad. For what it’s worth, I love them. They’re by Jennifer Jones, who I came across at the latest Bloomberg New Contemporaries exhibition, an annual showcase of the 50-or-so best artists freshly out of art school. I reached out to her and asked if she wanted to display some of her work and she said yes.

Karen, a regular, noticed the changes to the cafe walls. She pushed her wraparound sunglasses to the top of her head and peered at the pieces. I braced myself for a complaint. Every week, she comes in, complains about the prices, tells you how hungry she is and then how tired you look. “I like them,” she said, “but there’s something depressing about them. Something really sad.” I frowned. Whatever, Karen, I thought as I placed a green tea and a sausage roll on her table. I had forgotten about this interaction until I went to interview Jennifer Jones in her Stockwell studio.

We sat on small chairs in a large white space, which she shared with nine other artists. They were all part of the Associate Studio Programme, a scheme offered to ten UAL (University of the Arts London) graduates, that offers subsidised studio rent, artist mentoring, and studio visits by practising artists, gallerists, and curators, over two years. Jones applied as a graduate of Central Saint Martins (CSM). At first she wanted to study fashion and went to the London College of Fashion but didn’t enjoy the course. Drawn to the openness of CSM, she applied for both the fashion and fine art courses and got into the latter. Of the ten people on the programme, only one other person was in the studio that day. I set my phone on the table, pressed record, and asked Jones what she was working on at the moment. Within seconds, I would be proved wrong and Karen proved right.

“I’m really interested in looking into generational and family trauma. So like, domestic space and the home and how that impacts your identity, I guess. Not to overshare, but the inspiration of what got me into that was I found out in late-teenage-hood that my dad was abusive to me when I was a child. But, I didn’t know and I didn’t remember and so I was really confused about how I couldn’t remember something from my past. So this interest in memory and how family and trauma affects your memory and blanks things out or rose-tints the past, is why I’ve been going back into loads of family photos, snapshots, really nice happy family moments.”

I told her that I was surprised by this, omitting my thought about Karen. Her work struck me as pretty calm and happy.

“Yeah exactly,” she replied, “this is the thing I’ve been thinking about as well, it’s like, I guess it fits conceptually but then if no-one knows what I’m talking about it doesn’t really work. But my work is about rose-tinting the past and everything being presented as lovely and overly soft and kind and comforting, and then a hidden dark secret or past. With family, or family drama, you don’t talk about it outwardly and try to pretend like nothing’s going on, so that’s the concept of it. But then I think maybe I’m doing that a bit too much that my viewer’s not even aware at all that that’s what’s going on. I’m trying to make the work this idea of nostalgia and looking back on childhood with rose-tinted glasses but there being a dark secret.”

I asked whether making the work had helped her come to terms with the trauma, at all.

“Definitely in the way that it has forced me to think about it, whereas before my approach was always like, just move on, block it out, don’t think about it. It forces me to confront it, and also more and more having to talk about it, because obviously people talk about my work. That’s a funny thing as well, like, with this project it’s a lot harder to speak about than the work I was making in uni, that was completely different. I was looking at identity but from a really bird’s eye view of wide society, not personal at all: heavily researched, identity categories and AI and stuff like that. So that project was so much easier to talk about, because it wasn’t about me and uncomfortable things. Then after leaving uni you’re not getting asked about your work as much or why you’re making stuff or having to write about it, and I started actually making more personal stuff that was harder to talk about. But with things that are hard to talk about, I communicate it through the work. It’s more of a personal process now, but then the questions do still come and then it’s finding a way to explain it that makes sense but isn’t oversharing or telling someone something they didn’t want to know.”

I turned talk to her pieces in the cafe. “All three are in different mediums, did your consideration change when you approached them?”

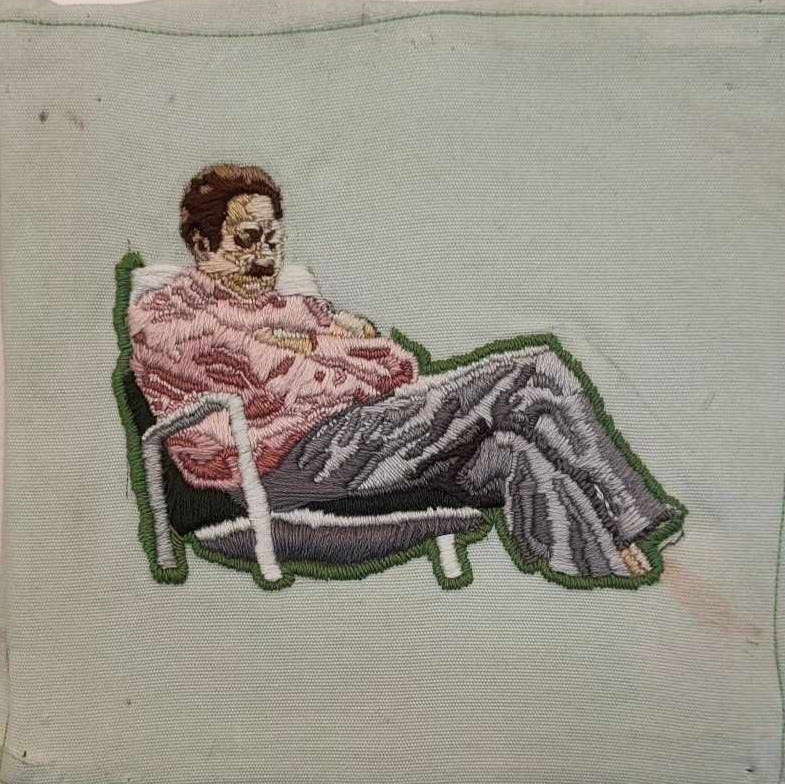

“Obviously they look really different but to me it’s a similar process for all of them. I guess it’s all about the handmade, and I’m working from all these recomposition-ed family photographs. But then, remaking them by hand, even when it’s in painting or tufting or embroidery, it’s still this process of looking really closely at something, working on recreating it for ages, and then the mistakes of the hand coming into it, getting further and further from the original image by replicating it. It gets less detailed and there are more mistakes, I won’t copy it exactly, it’s the error of it. To me, they’re all quite similar. I think I like the textiles work the most, it communicates this idea of the home, domestic objects, and comforting materials.”

Two textiles pieces hang in the cafe, Embroidered Grandad (embroidery) and Grandad Washing Up (tufted rug), best exemplifying the comfort and warmth Jones likes about that medium. Both only feature one figure, though, taken from one photograph. In pieces like It Didn’t Start With You, her painting in the cafe, separate family photographs are collaged onto a horticultural pattern to create an ethereal, surreal scene, reflecting Jones’ idea of disjointed memory and looking at the past and it not really making sense. Moving the conversation on, I asked what her goals for the future were.

“I definitely want to be exhibiting internationally, I want to travel for my art. I don’t know what that would mean necessarily, but something like: making art has allowed me to travel, meet new people, be in different contexts, learn different things, see different art worlds in different cities. Maybe being represented by different galleries in different countries, travelling between them, showing stuff. And, I guess, also having more public exhibitions, even though my work at the moment doesn’t lean towards that but I would in future really like to be making work that’s commissioned by councils for public sculptures. Stuff not in art galleries, my work being seen by the wider public, on the tube or… yeah, bringing art to people who don’t go to galleries.”

“Is that kind of thing important to you?” I asked.

“For sure. Coming from quite a working class background and not a very arty town, people not really thinking it’s for them or relevant to them or interesting, and trying to change that.”

“Have you experienced any strange disconnect between being an artist and the place where you grew up or the people you were around?”

“Yeah definitely,” Jones replied, “I think I’m getting used to it more now that I’ve been away from my home town for quite a long time. But when I first came to uni I was finding it really weird, I really didn’t fit in or, also, know what anyone was saying. In the lectures there’s, like, this art lingo but then I saw myself slowly slipping into it and speaking … it’s like a language that I learnt, it sounds dramatic but it’s like, people don’t speak like that.”

“What kinds of words?”

“Not even words but more the way… the really metaphorical and not-to-the-point way that people speak about art in lectures, you really had to decode what they mean rather than just saying plain stuff. But now I understand that that way of speaking does actually allow you to express yourself more, in a way, but it took me a while to follow a conversation. But now I’m fine.

“And then on the other side,” she continued, “what I’m doing and why I’m doing this and trying to explain it to my friends at home or to people who have jobs that pay money, where you go to work and get promoted… Whilst you’re at uni people understood like, ‘you’re studying, that makes sense,’ but then it’s like… ‘cause I work in retail as well and then I do this [art] and it doesn’t make me any money and people just don’t understand why I’m doing the programme when it doesn’t make money. ‘Cause it’s not school or uni, so it’s not education, but it’s also not a job so they’re like, what’s going on? And they’re like, why are you doing that if you’re not getting paid? To explain is quite alien to people, but then it makes me question myself when I also don’t have an answer of why I’m doing it, it also doesn’t make sense. It’s just what art people do, don’t worry. The concept of having to work towards something for ages without getting paid is something that’s quite strange to justify, even I don’t understand it yet, or when it will start becoming something I can sustain myself on, I don’t have a plan for that, so it’s hard to explain it to someone, for sure.”

This brought us quite nicely onto two questions I like to ask every artist I interview.

“So, what is an artist, in your mind?”

“I guess there’s two answers I have. One is, an artist is anyone who has a creative idea or a creative process that they use and makes things from it, if that makes sense. Like, thinks of a question, or has something that they want to figure out and then has a medium or an outlet that they use to explore that question or thing they’re interested in, which could range from model making to writing to making music, someone that just makes things about their interests. And then another side is, someone who… I don’t want to say ‘makes money’… Maybe someone that makes money from something that they create, but then I think that’s too broad.”

“And what is the role of the artist in society?”

“It’s about bringing people’s attention to something, that’s what I think. Trying to show people different perspectives or make someone think deeper about something they would maybe not think much about.”

“Nice one,” I said, “that’s probably enough.” I thanked Jones for her time and walked back to the train home. At time of writing, Karen hasn’t yet come back into the cafe. I don't think I'll tell her she was right about the art.

****

*I just work there, I don’t own or run it.

****

You can see Jennifer Jones’ (b. 1999. Chelmsford, Essex) artworks ‘Embroidered Grandad’, ‘It Didn’t Start With You’, and ‘Grandad Washing Up’ at the Mansion Bar and Cafe, Beckenham Place Park, south east London. If you want to get involved with the art in the cafe, message me.