In an old stable down an alleyway near Bond Street, with the rain dripping between champagne flutes onto the cobbles outside, we asked a man for a top up. He had longish hair and stood behind a blue dressing screen at the back of the room. Glasses were taken from us and placed onto a table. A bottle of champagne was ferried into his hands. He readied the bottle and twisted the cork, which was soon airborne. The bottle popped and the cork pinged high onto the wall behind him, before landing in an ice bowl. He smiled. “At least it didn’t hit the art,” he said.

We complimented the exhibition, thinking he was the curator. “It’s all Isaac,” he replied, inclining his head towards a man in a suit, sporting a thin moustache and slicked back curly hair, being pulled into conversations and exchanging numerous cheek kisses. He looked familiar, I thought. Had I met him?

The intrigue was a saviour of the evening. Boy was I glad there were two private views happening so close to one another. The first was a dud, the gallery was full of massive paintings that straddled abstraction and figuration that didn’t do much for me. Also, there was this guy with thin white sunglasses and a blue balaclava with noodles hanging over his mouth that made him look like Zoidberg, approaching strangers and telling them he didn’t like the paintings. Wanker, I thought. So we left and made our way to Belmacz gallery’s pop-up exhibition, down the road.

It was rammed. I stepped on people’s toes and tripped over their heels. You couldn’t help but overhear what people were saying. A man who introduced himself as a journalist as he pushed his way to the front of the champagne queue said to no-one in particular: “You know this is happening when Daniel comes.” I turned around and saw who he was talking about.

Above a sea of people towered Daniel (or at least, I assumed that was their name). A golden wire crown atop their head, Daniel moved slowly through the crowd. It was like seeing a mythical creature in the flesh. Eyes wide, I shuffled out of their way. I had actually seen them at another rammed private view last year, where my friend and I had referred to them as The Outfit, because they were wearing this enormous elaborate bedsheet dress. This time, a shawl peppered with Marilyn Monroe heads draped from Daniel’s neck to the floor. Anywhere they were felt like the centre of the world.

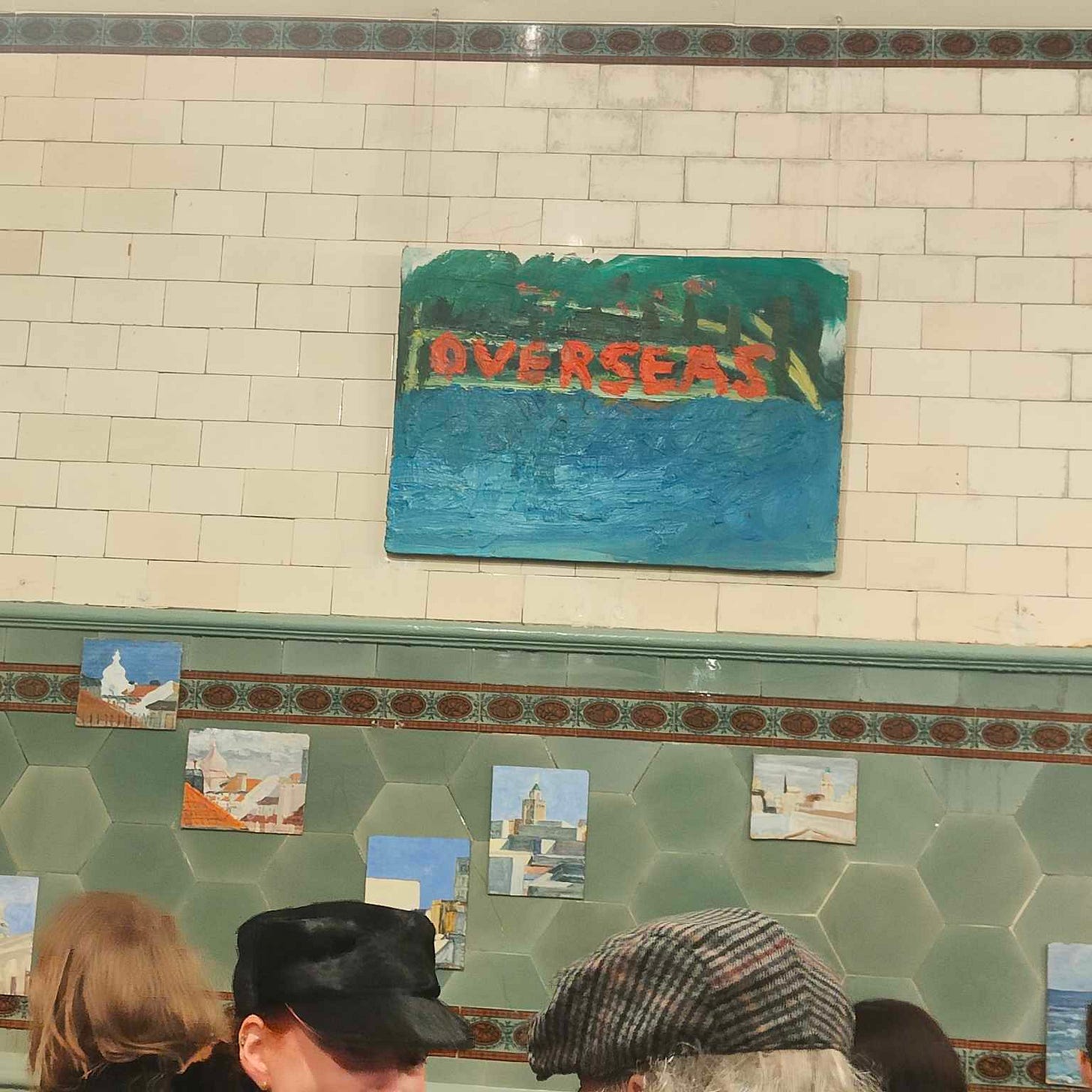

The art, yes, was good. It was a group show loosely collected around the theme of travel. They were pretty much all paintings. My favourite was this blue and green piece that had the word OVERSEAS written over it in orange letters. A series of little travel-scape paintings were dotted beneath it. Very nice. Towards the entrance were some nice pale pictures, of doorways and glimpses of people. I couldn’t make out which was by who because there weren’t any labels anywhere. Eventually I was handed a leaflet with the exhibition information, which stated that the show had been curated by one Isaac Benigson. “I knew I’d heard of him!” I said. Last year, I read an ES Magazine article about the ‘YLAs’, or Young London Artists - emerging artists, curators and gallerists in London’s art world. Isaac was part of it. Gosh, did that article make me bristle with fury.

The article opened with this fact that artists in the public sector were paid, on average, £2.60 an hour. “Uncapped rents are driving creatives home to their parents,” it read, “cuts to art education deepen and galleries grapple with spiralling costs”. Fair enough, I thought, it is tough. And then it listed the kids making it in this tough old business, including the literal child of Charles Saatchi and the country’s fifth wealthiest person under 35. To get ahead in the art world “the starting point is to get to know people in the industry: go to private views and meet them,” said the £758,000,000 heiress.

I watched Isaac glide around the room, never tripping over peoples feet or mumbling his words or making risky jokes (the Tom Glover triumvirate). He was born for moments like these and he wasn’t nearly the most privileged of the YLAs. He did go to a school where a year costs at least £30,000, though. If I think about it too much I just become depressed. As we were leaving, Isaac was just behind us, arm in arm with a friend, who said, “Pleasure, Isaac, pleasure.” Isaac laughed, before catching sight of someone he knew and calling their name, “Caspar! Caspar!”